Lebanon’s cedars are threatened by warming

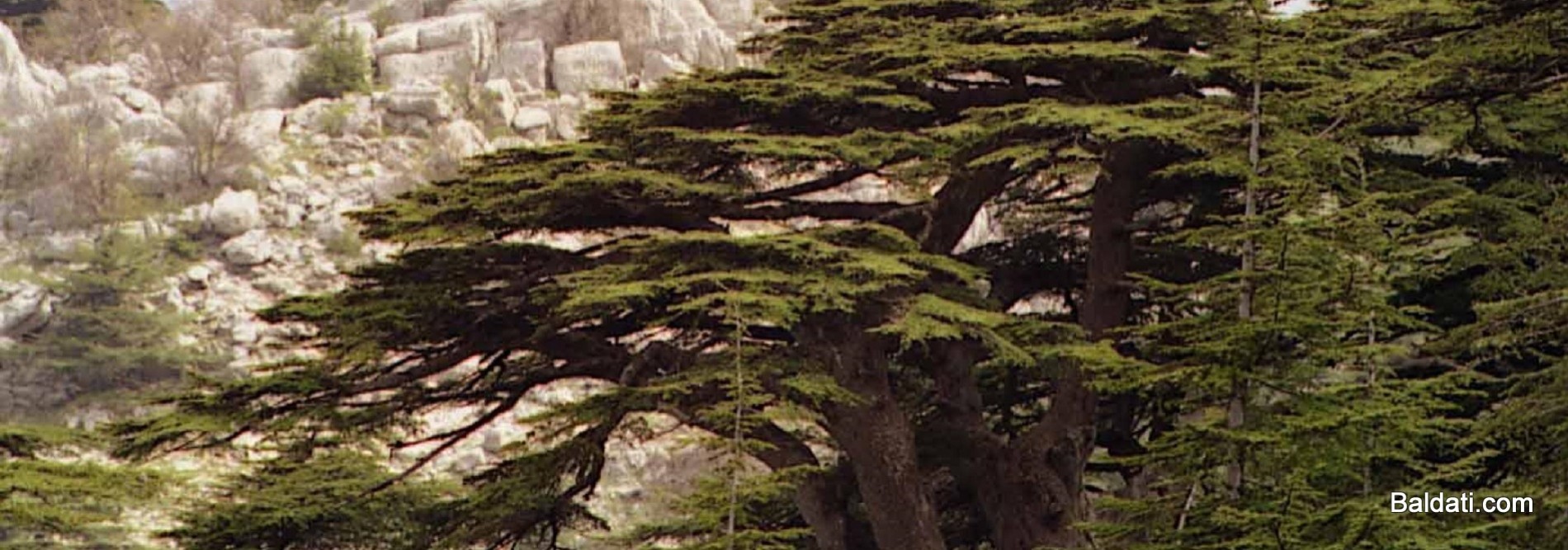

BAROUK, Lebanon - There's no escaping the cedar tree in Lebanon.

A cedar is emblazoned on the country's flag, and another on the planes of the national airline. It is on the currency, on passports and on all official documents. It is proudly worn on the uniforms of soldiers and crudely plastered on tourist knickknacks from ashtrays to fridge magnets.

Cedars also have played an integral part in Lebanon's volatile political life. Several Christian factions in the country's civil war adopted the cedar as their emblem; one called itself the Guardian of the Cedars. When Lebanese took to the streets to demand the withdrawal of Syrian troops in 2005, their protest was dubbed the Cedar Revolution.

And such is the importance of the cedar that one-time Druze warlord Walid Jumblatt, now a leading politician, planted land mines around the trees in his Shouf mountain fiefdom during the civil war era, to protect them from loggers, militias and other marauders.

But the imposing, majestic tree that has defined Lebanon since biblical times now faces a potentially bigger threat to its existence than war or political overkill.

Global warming, the scourge of ecosystems worldwide, also is endangering the ancient Lebanon cedars that are native to the Mediterranean, by pushing ever-higher the snow line in the mountains where cedars thrive and jeopardizing the fragile environment that sustains them.

"Until now we don't have a direct impact, but all the indications and observations of scientists, and the monitoring of the environment, suggest that within the next 10 years we will see a major impact on cedars from climate change," said Nizar Hani, scientific coordinator of the Shouf nature reserve in Barouk, from which the land mines have been removed.

Here, on steep mountainsides dotted with cedars young and old, anecdotal evidence of the threat is clearly visible.

Deep snow covers the uppermost reaches of the reserve, as it normally would at this time of year. But lower down, the snow is patchy or nonexistent.

Cedar cones need several weeks of snow cover every year to germinate properly. Yet this year's snow arrived late, in February instead of December, and many trees received only 10 days of cover or less, according to Hani.

Typically, cedars thrive at an altitude of 4,000 to 6,000 feet. This year's snow descended only to a level of 5,000 feet, leaving lower trees without any cover at all.

Another problem is that the lack of snow encourages the proliferation of unwelcome pests. In the most alarming instance of the threat so far, scientists say, a plague of sawflies munched through the cedar forest of Tannourine earlier this decade, killing 12 percent of the trees before it was contained.

The infestation was a direct result of warmer temperatures on the life cycle of the cedar-eating Cephalcia sawfly, said Nabil Nemer, an entomologist at the American University of Beirut who is researching the still little-understood effects of climate change on the cedar forests.

The hardiness of the cedar is legendary, and no one is predicting its demise any time soon. The oldest tree in Barouk, with a trunk spanning nearly 50 feet, is estimated to be 2,000 years old. Several trees in reserves farther north are believed to be even older.

"This is a very strong tree," said Nora Jumblatt, the politician's wife and a leading figure in the cedar conservation effort. "It is a witness to history that personifies Lebanon and the Lebanese soul of resilience and endurance."

Bigger threats to their survival have already passed.

The Phoenicians chopped them down to build their ships. King Solomon had them felled to build the temple of Jerusalem, according to the Bible. The Pharaohs of Egypt plundered them for their tombs, the Romans exploited them to construct their empire and the Ottomans used them to build their railways.

Now just 5,000 acres of cedars remain, most of them contained in a handful of protected reserves high in the mountains. More research is urgently needed to understand the effects of global warming if these last trees are to be preserved, said Nemer, the entomologist.

"The cedar tree is the symbol of our country, and it would mean a lot if we were to lose it," he said. "It would be like losing our identity."

LIZ SLY CHICAGO TRIBUNE